Suicidal OCD is a form of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) where people experience unwanted, intrusive thoughts about suicide. These thoughts can feel vivid and alarming, but they do not reflect a genuine desire to die. Instead, they trigger fear and anxiety, leading people to question their safety and perform compulsions to feel reassured. According to research, 16% of people with OCD report having obsessions and compulsions related to suicide.

Understanding the difference between suicidal OCD and true suicidal intent is essential for getting the right help and treatment.

What is suicidal OCD?

Suicidal OCD is a subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in which a person experiences recurring, unwanted thoughts, images, urges, feelings, or sensations about suicide. Unlike genuine suicidal ideation, these thoughts are ego-dystonic, meaning they go against a person’s true desires and values. People with suicidal OCD fear harming themselves, even though they do not want to die.

Common signs and symptoms of suicidal OCD

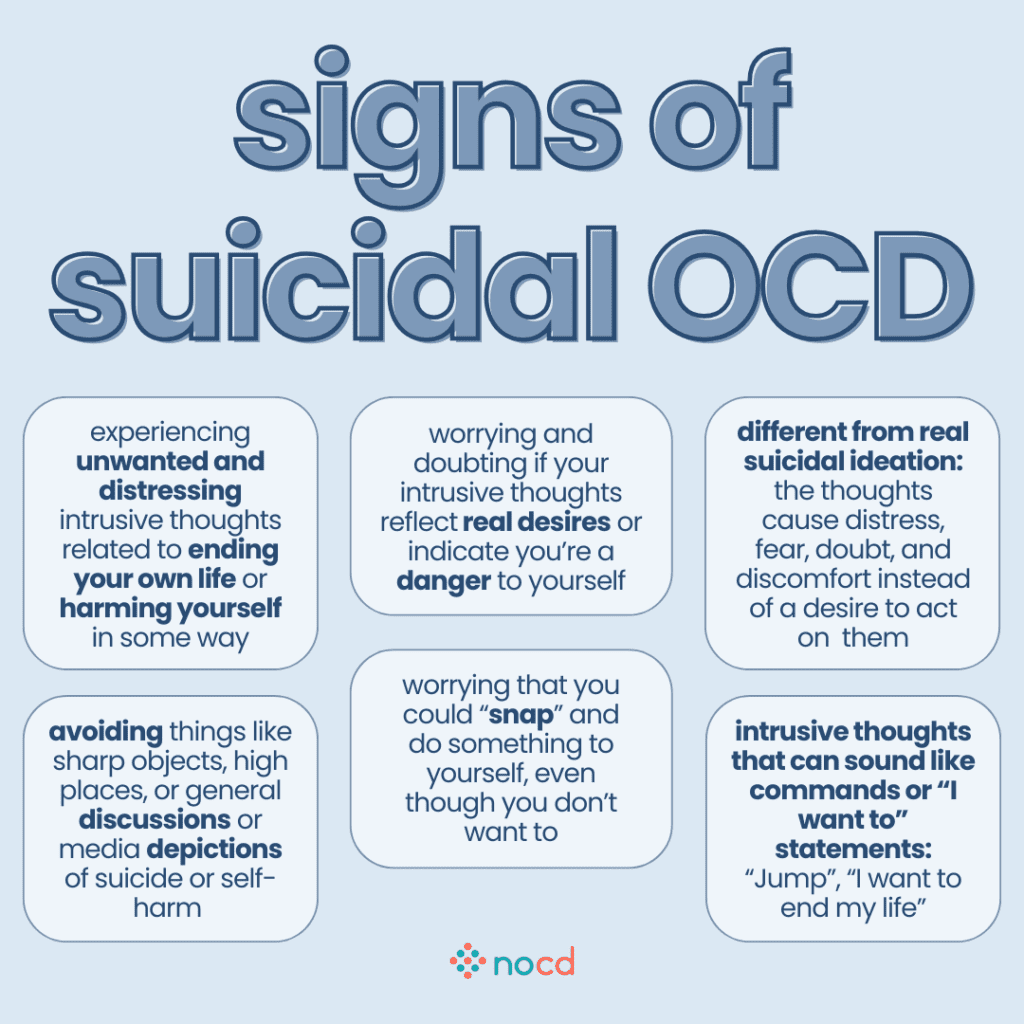

While this is not an exhaustive list, people with suicidal OCD may experience the following symptoms:

- Intrusive suicidal thoughts that appear suddenly and feel distressing.

- Mental compulsions, such as overanalyzing whether they are suicidal.

- Reassurance-seeking, repeatedly asking others if they seem safe or capable of self-harm.

- Avoidance behaviors, such as staying away from knives, bridges, or medications.

- Checking rituals, monitoring their own mood or urges to confirm they don’t want to die.

These symptoms are not signs of a genuine desire to end one’s life—they’re the expressions of OCD.

Is suicidal OCD the same as being suicidal?

It’s important to reiterate that there are differences between suicidal OCD and suicidal ideation. Having suicidal OCD does not equate to being suicidal.

“Suicidal ideation is something that we take very seriously, so we want to know what’s going on,” says Patrick McGrath, PhD, NOCD’s Chief Clinical Officer. “Does the person have an actual plan, intent, a desire, a want [to end their life]? On the other hand, if they are asking themselves ‘what if’ questions followed by some kind of compulsion, be it a mental or physical compulsion—that is OCD.”

What triggers suicidal OCD?

Suicidal OCD can be triggered by stressful life events, exposure to news about suicide, or even random intrusive thoughts. OCD likes to latch onto sensitive topics, and suicide is one of the most feared. The brain misinterprets intrusive thoughts as dangerous, causing anxiety and compulsive responses.

How is OCD diagnosed?

Suicidal OCD is diagnosed by a licensed mental health professional. Diagnosis involves ruling out suicidal ideation or self-harm risk, then identifying patterns of intrusive thoughts and compulsions consistent with OCD. Structured interviews and self-report assessments may be used to clarify the difference.

Treatment for suicidal OCD

The most effective treatment for suicidal OCD is exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy. ERP is a specialized form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) proven to be effective for OCD. General CBT, if not tailored for OCD, can sometimes be unhelpful or even worsen symptoms.

Studies show that ERP therapy is highly effective, with 80% of people with OCD experiencing a significant reduction in their symptoms.

Other approaches that may help include:

- Medication (typically SSRIs)

- Mindfulness-based strategies

- Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)

These are typically done in combination with ERP therapy, depending on the individual’s needs.

Severe or treatment-resistant suicidal OCD may benefit from the following therapies:

- Intensive outpatient programs (IOPs)

- Partial hospital programs (PHPs)

- Residential treatment centers (RTCs)

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS)

- Deep brain stimulation (DBS)

- Gamma knife radiosurgery (GKRS)

Find the right OCD therapist for you

All our therapists are licensed and trained in exposure and response prevention therapy (ERP), the gold standard treatment for OCD.

Coping strategies for suicidal OCD

While professional treatment is essential, people with suicidal OCD can also benefit from:

- Limiting reassurance-seeking to prevent reinforcing the OCD cycle.

- Building a support system with trusted friends, family, or peer groups.

When to seek immediate help

If someone is experiencing thoughts of wanting to die or making plans to harm themselves, this is not OCD—it’s suicidal ideation and requires immediate attention. Call 988 in the U.S. for the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline or go to the nearest emergency department.

Bottom line

Suicidal OCD is not the same as being suicidal. It involves unwanted, intrusive thoughts about suicide that cause distress but do not reflect a desire to die. With treatments like ERP therapy and medication, people with suicidal OCD can reduce their symptoms and reclaim their lives.

Key takeaways

- Suicidal OCD involves intrusive thoughts about suicide that are unwanted and ego-dystonic, not a true desire to die.

- The condition is different from suicidal ideation, which reflects genuine intent or planning to end one’s life.

- Effective treatments include exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy and medication such as SSRIs.

- Immediate help should be sought if someone is experiencing active suicidal thoughts or making plans to harm themselves.