When you think about your relationship with food, you might have certain preferences or behaviors that lead you to wonder, “What’s really going on here?”

Maybe you have a habit of eating foods in a particular order, or only eating at set times. Or perhaps you worry that certain foods will make you sick—you don’t have any evidence that they will, but you can’t shake the feeling. Or you strictly avoid specific foods, while at the same time you insist on eating one food item or food group for several days or weeks at a time.

Do you have an eating disorder? Is it obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)? Could it be both?

If you’ve ever asked yourself questions like these, you’re not alone. The distressing thoughts, rituals and behaviors that result from both OCD and eating disorders can look quite similar — so similar, in fact, that it’s easy for people who are struggling (and even clinicians) to feel confused. But understanding the root cause of your issue is critical to getting the right help, says Hilary Stein, MSW, LCSW, a therapist and clinical lead for eating disorders at NOCD, a virtual treatment provider for OCD and related mental health conditions.

Let’s take a closer look at the relationship between OCD and eating disorders so you can get on track to finding the help you need.

Do OCD and eating disorders commonly co-occur?

Yes, they do. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the guide that professionals use to diagnose mental health conditions in the US, the incidence of OCD is higher among people who have another diagnosed mental health condition, including an eating disorder. In fact, research suggests that around 11% of people with OCD have an eating disorder.

The reverse has also been studied. A 2020 review found that roughly 15% of those with eating disorders had OCD at the same time, and 18% of people had what the scientific community calls a “lifetime comorbidity”—meaning that those with an eating disorder experience OCD at some point in their lives. In some studies, when researchers followed up with study participants later on, they found that comorbidity rates were even higher — inching up toward 38%.

When someone with an eating disorder also has OCD, the OCD can affect how the eating disorder manifests. “We see lots of more compulsive, ritualistic behaviors going on—like orderliness, or specific ‘just right’ behaviors,” says Stein. For example, you might feel compelled to purge a specific number of times each day at precisely the same times.

What’s the connection between OCD and eating disorders?

While there’s no one explanation that applies to everyone, here are some of the factors that overlap:

- Genetics: A 2021 study found that eating disorders and OCD may be related to some of the same genes.

- Disposition: Research suggests if you’re prone to negative emotions, you may be more likely to have both OCD and an eating disorder.

- Unwanted thoughts: Amid eating disorders, thoughts about food and attaining a certain body can be unwanted and highly distressing. Similarly, intrusive thoughts are symptoms of all types of OCD and can turn into obsessions.

- Personality: Shared personality traits—like perfectionism and neuroticism—may also help explain the overlap.

How does perfectionism show up in both OCD and eating disorders?

Well, people with perfectionistic tendencies may feel a sense of control by limiting their food intake or exercising compulsively — common behaviors associated with eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. And in the case of OCD, someone with “Just right” OCD (as well as other subtypes of OCD) may have obsessions and compulsions that revolve around things being exact or precise. Chewing food a certain number of times or counting every almond until it feels “just right” can feel like a necessity for some people with OCD.

Is food-related OCD always focused on weight?

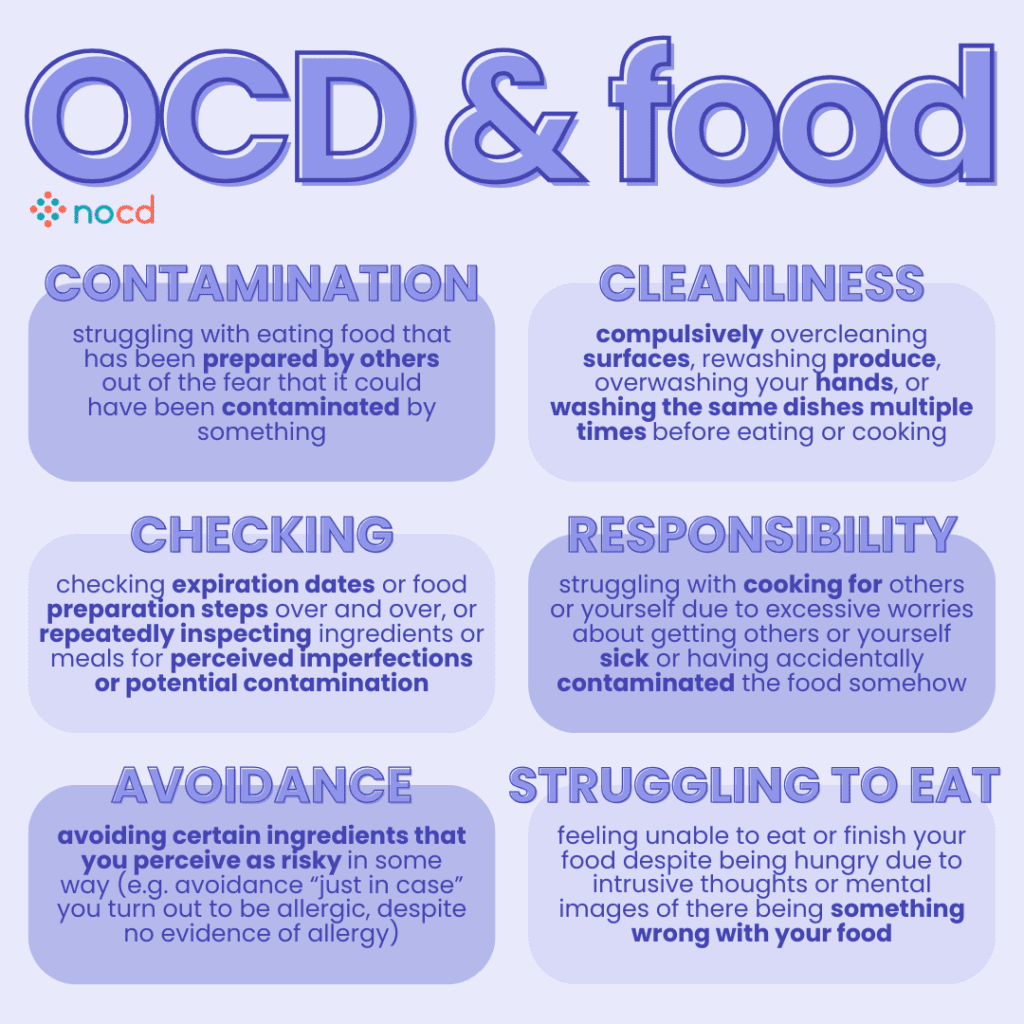

No. In fact, an important thing to note about the way people experience food-related obsessions and compulsions in OCD is that they may be symptoms of Contamination OCD, Health Concern OCD, or Hoarding OCD—subtypes of OCD that aren’t usually focused on weight and body. For instance, someone with Contamination OCD or Health Concern OCD might avoid eating specific foods that they associate with uncleanliness or the possibility of getting sick. And a person with Hoarding OCD might have the compulsion of buying certain foods in multiples of three (or another number that they have assigned a significance to).

Common food-related OCD obsessions:

- Fear of foods that may carry diseases

- Fear of not digesting food

- Fear that something bad will happen if you’re not the one preparing your food

- Fear of having a harmful “reaction” to certain foods

Common food-related OCD compulsions:

- Storing an excessive surplus of specific food items, for fear of running out

- Avoiding food prepared by anyone else

- Engaging in time-consuming rituals as a part of any OCD subtype and “forgetting” to eat

- Practicing repetitive behaviors like touching or arranging food a certain way in order to prevent something “bad” from happening

How to tell if it’s OCD, an eating disorder—or both

Since the symptoms of eating disorders and OCD can overlap, it’s possible to be misdiagnosed with one disorder when you actually have the other—or maybe both. “That’s why it’s so important to see a doctor or mental health counselor who is trained in both OCD and eating disorders—so you can get the correct diagnosis,” says Kimberley Quinlan, LMFT.

That said, these examples can provide some helpful clues about what’s going on:

| Eating Disorder | OCD |

|---|---|

| You may organize your days around eating times and avoid certain foods, often for fear of gaining weight. | You might avoid certain types of foods due to anxieties about germs or getting sick. |

| You use food rituals in an attempt to feel safe—like eating the same salad every day because you know the calorie count. | You may feel the need to eat the same salad for lunch every day because you’re terrified that something bad will happen if you don’t. |

| You might count the number of bites you take in order to limit your intake and control your weight. | You might count the number of times you chew your food until it feels “just right”—but it isn’t necessarily tied to weight concerns. |

| You have unwanted and distressing thoughts that are mostly ego-syntonic, which means that they’re generally in line with your values. | You have unwanted and distressing thoughts that are typically ego-dystonic—meaning that they don’t match up with your values or view of the world. |

| You might see your behaviors as beneficial or view them as a form of discipline. | You tend to see your thoughts as irrational but are afraid that somehow they might be true. |

How eating disorders and OCD are treated

Here’s the bright spot: “OCD and eating disorders are highly treatable and have well-studied therapies developed specifically to support folks toward recovery,” says Stein. OCD and eating disorders are treated differently, but don’t worry, we’ll walk you through how to get help.

The best treatment for an eating disorder

One vital part of eating disorder treatment is getting your weight and nutrition back to a place your doctor finds healthy for you. Treating an eating disorder might include therapy, nutrition education, medical monitoring—or a combination of all three. Sometimes medications are also needed.

One common form of therapy for eating disorders is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). CBT focuses on the behaviors, thoughts and feelings related to your eating disorder—and helps you shift to healthier ones.

While there are many forms of CBT, Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) is a specific type that may be particularly helpful. DBT is aimed at helping you build better coping skills such as learning how to tolerate distressing feelings without engaging in disordered eating behaviors.

Some therapists even use exposure therapy for eating disorders—which is similar to the OCD treatment we’ll discuss below. Exposure therapy involves gradually exposing you to feared situations—such as eating outside of your comfort zone—in a safe and controlled manner.

The best treatment for OCD

The therapy that’s considered the gold standard for treating OCD is Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) therapy. ERP is an evidence-based therapy, which means that extensive research has been done to prove that it’s successful. This specialized treatment is unlike traditional talk therapy or general cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). And without practicing ERP specifically, it’s very likely that your OCD will get worse, not better.

ERP works by gradually exposing you to what triggers your specific fears, and teaching you response prevention strategies to cope with your distress. For example, one of the first exposures you do might simply be to watch a video of someone who is eating one of your “off-limits foods.” Over time, you might try a new food, or stop hoarding foods that you worry won’t be available one day. You will never be forced into any exposure before you’re ready, but you will be encouraged to take steps that move you toward recovery. By learning to resist your compulsions, you begin to realize that they were never even necessary in the first place.

Stein recalls a patient who needed to eat food in a very specific way—food couldn’t touch, and they had to eat their food in a particular order and speed. First, she asked them to simply touch their foods out of order. Later, they took bites, and ultimately ate entire meals out of order. Over time, the patient became comfortable eating without having to follow any of their former rules and rituals.

“Before ERP, this client barely had motivation to eat because their rituals were so exhausting. But after treatment, they were finally able to eat freely again,” says Stein.

How to get help for OCD and an eating disorder

If you’re diagnosed with both, Stein and Quinlan say it’s best to combine modalities to treat your OCD and eating disorder.

“The best approach is to have both clinicians work together as a treatment team with you,” Stein explains. That’s because the treatments that work for eating disorders aren’t the same as the therapies used for OCD—so it’s crucial to involve an OCD specialist. “When we’re treating anything that co-occurs with OCD, we always have to be careful that the other clinician isn’t accidentally reinforcing some of the OCD pieces,” she adds.There’s no question that OCD and eating disorders are two very challenging mental health issues. But as Stein can attest—having worked with many people who have recovered—it’s quite possible to take your life back from both.